Addressing loneliness across social housing residents

Loneliness is prevalent across the UK and has been shown to have significant negative impacts on individuals and communities. That harm is of such concern that the nation even has a loneliness minister. What can be done to prevent loneliness in neighbourhoods?

To mark the publication of the Community Support & Life After Lockdown report, we’ve been talking to the experts that advise us on the key themes for the Resident Voice Index™ project. We spoke with loneliness expert, Dr Deborah Morgan, Senior Research Officer at the Swansea University Centre for Innovative Ageing about the results from this survey and how to address loneliness.

How the Resident Voice Index™ measured loneliness

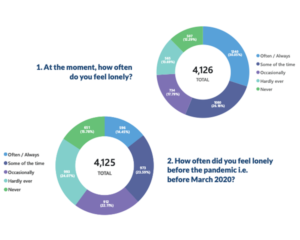

Two questions were included, derived from established measures of loneliness. They asked how lonely people felt in November 2021 and how lonely they felt prior to March 2020, allowing us to compare the rates of loneliness from these two points of time.

What stood out from the results was the sheer volume of people that reported feeling lonely (56%). Even prior to March 2020, the number was still very high at 38%. Over that time there was an 18% shift in people who entered the ‘most lonely’ categories and expanding out from there, a more general shift in loneliness was recorded, even for those who didn’t fall into those ‘lonely’ categories. Overall, 40% of all respondents reported feeling lonelier in November 2021 than they had before March 2020.

The magnitude of loneliness

Deborah explains that, “Loneliness is something that we all experience at some point. It’s a normal human emotion, although it’s not one we often talk about. Obviously, we’ve seen much more of it during the pandemic.”

“Loneliness in its chronic form – when it goes beyond a time of 12 months or more – that’s when we begin to see it impacting on physical and mental health. Some people experiencing chronic loneliness will experience depression, they may have physical symptoms that are unrelated to underlying health conditions. This explains why you see more people who are chronically lonely attending GPs and having tests when there’s nothing clinically wrong with them.”

“In this chronic form, it’s a really difficult thing to recover from. We see people losing confidence, their self-esteem plummets. That in turn impacts on their ability to interact with other people, they become more fearful of rejection.”

The key thing to remember is loneliness is something that everybody experiences, it’s perfectly normal. It’s nothing to be ashamed of.

– Dr Deborah Morgan

“You can recover from it, you just might need a little bit of help. We have a role to play ourselves because if we talk about our own experiences of loneliness, it will reduce that stigma, which in turn will help people recover.”

The difference between loneliness and isolation

These two phenomena are often conflated – and Deborah wants us all to know the difference.

“Loneliness is when there is a mismatch between the quality and the quantity of the relationships we’d like to have and those we actually have. It means somebody could have a small social network and never be lonely because that network meets all of their needs. Whereas somebody could have a huge network of family and friends and still experience loneliness because the quality of the relationships is not what they’d hope for. In contrast, social isolation is when you have an absence of a social network or a very small social network.”

Are we serving our younger residents?

Across the Resident Voice Index™ studies, those under 35 have reported more negatively than other age groups for all measures. In the Neighbourhoods & Communities survey they were the least likely to report feeling safe, feeling like they belonged to their neighbourhood or to care about being involved. In the latest survey, a similar trend emerged, where they reported as less resilient, less optimistic, and lonelier. In terms of loneliness, the shifts of the under 35s into the ‘lonely’ categories and the general shift in loneliness was more pronounced.

For Deborah, that wasn’t a surprise, “When looking at loneliness across the population, there is a U-shaped distribution with prevalence high in younger and older people. There are significant numbers of transition points at both stages of the life course that will influence and increase the likelihood of people being lonely. But that doesn’t mean people in the middle won’t experience loneliness.”

Places to meet, places to breathe

Administrations, such as local governments, planners and housing providers have a part to play. The built environment can help prevent people from becoming so lonely. A trend from the residents that took the survey was a desire for more green spaces. These are spaces where people can interact with nature and bump into one another, building connections, like chance encounters on a park bench.

The quality of environments could go a long way in facilitating connection, delivering high-quality environments where people want to spend more time. Deborah’s recent work has explored this topic. She has been, “Looking at low carbon homes; both new build and those being retrofitted. We also measured loneliness and isolation. People seemed to be much more likely to engage with neighbours in a new home than they were in an existing one.”

“Additionally, because everyone in the new builds was in the same boat, having moved in at roughly the same time, they were able to build those connections with one another. They set up WhatsApp group sharing, they’ve got to know their neighbours.”

Work done by Ade Kearns in Glasgow studied loneliness in very deprived areas, looking at people’s trust in the neighbourhood and trust in their neighbours. The built environment can send out implicit messages about a place, for example that ‘it’s not safe’.

Stemming from Wilson and Kelling’s 1982 ‘Broken Windows Theory’, the Glasgow study found that seeing broken streetlights, lots of rubbish, or graffiti sends a message that your neighbours aren’t to be trusted. “A poor built environment makes people fearful; residents don’t necessarily want to go out and spend time in any available communal space. Whereas, if you live in a much nicer area, where there’s places to sit and chat, adequate lighting etc you’re more likely to go out and engage.”

For Deborah, a main proposal for housing providers, planners and local authorities was to build high-quality neighbourhoods that design in connections. “When we’re planning new housing estates or redeveloping existing ones these things are really important to think about.”

The Community Support & Life After Lockdown report is out now. Read the full loneliness results alongside discussion of why a high-quality built environment matters here. If you would like to speak directly to MRI Software about getting involved with the Resident Voice Index™ project, contact us at info@residentvoiceindex.com

Royal Borough of Greenwich frees up 40% of administrative time to better manage Homelessness cases.

The Royal Borough of Greenwich, serving over 270,000 residents in London, manages around 20,000 households. It is committed to improving social housing quality and availability, amplifying resident voices, and empowering tenants and leaseholders. Add…